Helping Sadek find his voice through inclusive education

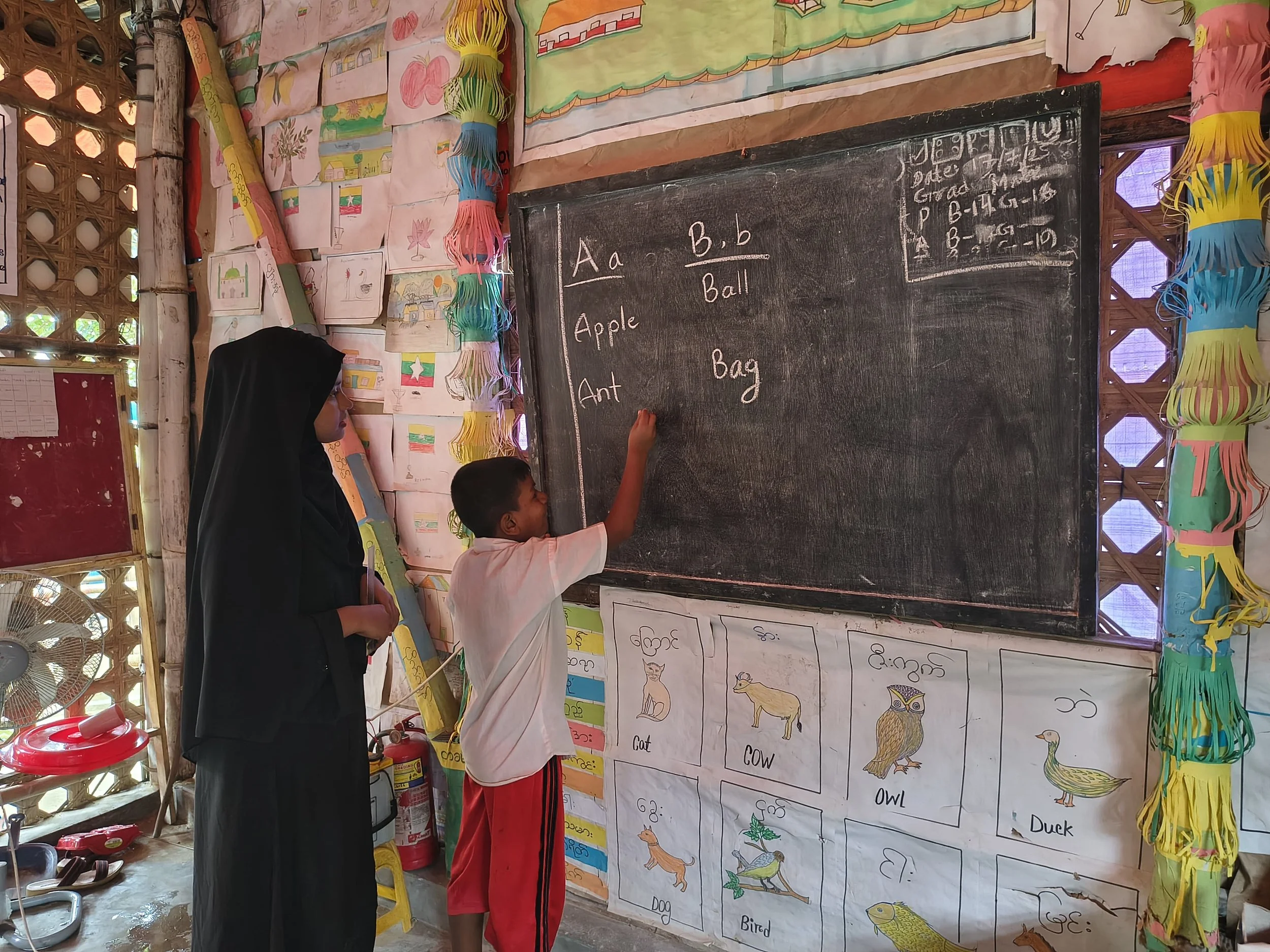

Above: Sadek* answers a question on the board in front of his grade two classmates. Credit: Abdullah Khan/YPSA/Save the Children

Above: Sadek*, who is now in grade two, participating in class. Credit: Abdullah Khan/YPSA/Save the Children

Above: Sadek* with his teacher Jahangir*. Credit: Abdullah Khan/YPSA/Save the Children

“When my son first called me ‘Amma’ (mother), I couldn’t hold back my tears. It was the first time he ever said it, after so many years of silence,” shared Roshida*, a Rohingya mother living in the refugee camps of Cox’s Bazar.

For Roshida, that simple word carried the weight of years of fear, uncertainty, and longing. Her son, Sadek*, was born with an intellectual disability and spent his early years locked in a quiet world of his own. She worried not just about his future in the precarious reality of the camps, but whether he would ever connect with his family, speak, or even recognise his mother.

Sadek was just a year old when his family was forced to flee Myanmar during the 2017 crisis. Carried in his mother’s arms, he was too young to understand that his family had become refugees, but life in the congested, resource-strapped camps of Bangladesh added layers of struggle, especially for a child with a disability.

“We tried many times to enroll him in the learning centres here,” Roshida recalled. “But each time, they said they weren’t able to help him. We started to believe that maybe it was his kismot (fate) to remain like this.”

Above: Sadek* participates fully in the classroom, despite his disability. Credit: Abdullah Khan/YPSA/Save the Children

In many camps, learning facilities were not prepared to accommodate children with disabilities. Teachers lacked training, and classrooms weren’t equipped with the tools needed to support diverse learners. Sadek remained excluded, watching his siblings and other children go to class while he stayed behind.

This changed when Sadek was six years old and he began attending a Learning Centre (LC) supported by the Australian Government through the Australian Humanitarian Partnership. The LC was led by Save the Children and implemented by local partner Young Power for Social Action (YPSA), with technical guidance from the Centre for Disability in Development (CDD).

This LC took a different approach and developed an Individualized Education Plan (IEP) for Sadek that set realistic learning goals. The LC also provides teachers with practical training on inclusive education and the use of Accessible Educational Materials, ensuring they were ready to meet Sadek’s needs.

Jahangir*, a Rohingya teaching volunteer at the centre, remembers his first impression of Sadek.

“When he arrived, he couldn’t speak, didn’t know his name, and avoided the other children. I had just received training on inclusion, but I was still unsure if I could help him,” he says.

Determined not to give up on Sadek, Jahangir used simple visual aids, patient repetition, and interactive activities to engage the young boy.

The centre that Sadek was attending also offers rehabilitation support and held awareness sessions with other parents and community members to foster understanding around disability inclusion, creating a safe environment for Sadek and other learners like him.

Over time, with the consistent support of his teachers and mother, Sadek began responding to familiar voices. Then came the breakthrough that Roshida remembers so vividly – he began to speak.

“We had almost accepted that he might never speak or learn, but now, every word he says feels like a gift,” she says.

Gradually, Sadek learned to say his name, identify objects, and participate in class activities. Now in grade two, he not only learns alongside his peers but also plays and laughs with them, something that was once unimaginable to Jahangir.

“Seeing Sadek now raising his hand in class, smiling, making friends, it’s a big change,” Jahangir shares proudly. “His progress changed me too. I learned that every child can learn if we give them the right support.”

For Roshida, the transformation is nothing short of life changing.

“I don’t worry the same way anymore. Now I believe my son has a future. He is learning, he is loved, and he is not alone,” she says.

* Names changed